Article originally published in the NCDA Career Developments, a publication of the National Career Development Association.

Does college and career readiness (CCR) look like it did during your youth? That question drives this article as career development charts its course into its second century. Shifting the focus of CCR beyond youth, time specific events, and graduate “destination rates” is proposed here. “Career readiness has no definite endpoint. To be career ready requires adaptability and a commitment to lifelong learning” (Career Readiness Partnership Council, 2012). Life design theory, narrative practices, and understanding changes in learning, work, and “ageless aging” (Leider 2014) have coalesced to emphasize readiness for a lifetime of transitions.

Policy makers see CCR as aligning curriculum with expectations to raise test scores. Employers hope CCR will meet workforce needs and create middle class jobs, and parents seek assurance that students will qualify for name-brand colleges and find livable wage employment.

Historically, CCR has focused on college admissions and financial aid, career pathways, and navigating the college admission process, “yet the increased focus on college and career readiness, combined with the complexity of the challenges associated with the topic, have led to a rapidly expanding college and career readiness community, rich with resources yet replete with confusion” (College and Career Readiness and Success Center, 2012).

Challenges to Defining and Understanding Readiness

“Readiness” is complex. Untrained in career development, administrators often define readiness as preparedness for college and job placement. However, career counselors and specialists know the true measure of success is stimulating learners’ self-awareness and encouraging intentional exploration for designing meaningful lives. We know that for all learners (especially youth) self-awareness and clarification precede curiosity, imperative to exploring learning and career options. With curiosity, college and career advice, career information, and career fairs become more than “information dumps” into resistant minds. Without curiosity and self-awareness, learners are more vulnerable to peer pressure, external rewards, and less able to find a fit between interests and natural abilities.

Readiness to Explore FIT

Understanding oneself, learning and work options, and one’s fit is challenged by gender-based circumscription of aspirations, career decision making readiness, and school to school or school to work transitions (Turner & Lapan, 2013). These issues shape making meaning from experience, informal feedback, and career assessments. Nonscientific assessments can fail to generate educational and occupational options for exploration, especially important to clients with limited work knowledge (Metz & Jones, 2013).

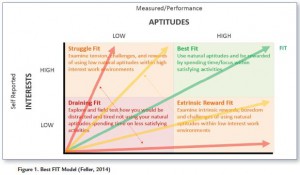

Substandard work performance due to mismatched abilities raises the importance of matching abilities with ability requirements of jobs (Swanson & Schneider, 2013). As research has shown, regardless of age, learners aware of their interests and natural aptitudes are more likely to find their FIT. The Figure 1. Best FIT Model illustrates the relationship among self-awareness, interests, and aptitudes (Feller, 2014).

Moreover, the Best FIT Model correlates strongly with focused learning, and greater ease in college and career transitions. The Latitude (www.youscience.com) program, which uniquely measures natural aptitudes, demonstrates how “FIT” levels encourage successful blending of personal interests and aptitudes in college and career choices. Within an economy unable to create enough jobs to match aspirations, employees struggle to achieve their best FIT. This is evident by relatively high under/ unemployment rates, increased frequency of adult career transitions, and encore careers. Such economic pressures often lead to early foreclosure on potentially less fulfilling career choices. Connecting learners’ self-concept to a meaningful life of purpose early is important, particularly as evidence shows that effective career interventions allow learners to proactively manage career transitions (Whiston & Blustein, 2013).

Youth Focus of CCR is Short Sighted and Narrow

As “students” face career decisions, the college prep track and career and technical education (CTE) duality remains unfortunately tenacious, and liberal arts or job preparation advocates remain steadfast to their chosen “sides”. As career development professionals, the question of obtaining a liberal arts education versus more specific job preparation needs to be viewed not as a “better or worse” choice, but rather as “equally important” options. The increasing number of four-year post-secondary graduates returning to technical and certificate programs as “reverse transfers” confirms this point. Learners of all ages are best served when “college” is universally replaced by “post-secondary education”. College is a place, whereas post-secondary is a continuous kind of learning.

Today, all of us no matter our age need to embrace lifelong learning, pursue self-understanding (see www.personalitydimensions.ca), and harvest psychological capital to thrive in The Next America (Taylor, 2014). In essence, we all need to be in a continual state of readiness for change as we seek community, relationships and personal growth within the “purpose economy” (Hurst, 2010).

The boundaries of work, learning and play are blurred. Technology increases information access (see www.cdminternet.com) that is readily assimilated into younger lives, leaving less tech savvy family members behind. With smartphone in hand and ever-present email, differentiating work from learning or play is difficult. The home office and workplace increasingly cross. Relatively secure, stable 8 to 5 jobs, overtime and wages that increase with age are no longer the norm. Moving up the career ladder is a less frequent route to social mobility. Wealth and class distinctions are more bifurcated across neighborhoods, and careers are rarely separately boxed into timeframes of education, then work, then retirement. The need for readiness looks very different from my high school days when it focused on youth, at one point in time, as they decided their post high schools plans.

CCR is best started in early childhood (www.missouricareereducation.org/project/guidelsn/cd1), and the goal of making high school matter is essential (Stone & Lewis, 2012). Yet, practice reminds career professionals that CCR spans the lifetime. An approachthat goes beyond interest-centric tools for traditionally aged students, and acknowledges workplace change and America’s demographic overhaul is necessary for learners to navigate a life of college (learning) and career (transitions).

Frequent and Complex Adult Transitions

In addition to the multitude of life and career transitions of youth, the same navigation and uncertainty exists for learners of all ages. Each life stage brings new questions about self-understanding and readiness for intentional exploration. Without continuous learning and a sense of purpose from paid or unpaid work, transitions leave individuals with “career pain”. The middle-aged learner and career-changer often experiences more stress, and an extended work life because of financial insecurity or workplace change. Aging is increasingly less determined by chronological age than by markers of failed health (e.g., loss of mobility), leaving many adults reimagining their life through choices, courage, and curiosity.

America’s aging population further accentuates that learning and work transitions are not a one-time event. Career development programs targeting only youth at one point in time leave many adults and 50% of urban students of color and poverty who drop out of schools unserved (Dobo, 2014). As career counselors and specialists, it is critical to understand that readiness precedes ALL client transitions.

Readiness to Design a Life

With increased frequency, youth and adults understand that work is a critical component of a well-designed, meaningful life. Designing a life employs three psychological tenets of individual differences, lifespan development, and narrative. Savickas’ work has generated international leadership and offers an approach for learners to fit work into their life design. Tools that help clarify life priorities and support narrative storytelling to create readiness include:

Help Clarify Life Priorities

- My Career Story: An Autobiographical Workbook for Life-Career Success (Savickas & Hartung, 2012)

- Narrative approaches including:

- Life Lines

- Card Sorts

- Elbow to Elbow Resume Development

- Life Role Analysis

- Career Genograms

- Life Reimagined – lifereimagined.com

Narrative Storytelling to Create Readiness

- What Color Is Your Parachute? (Bolles, 2014)

- Hope Centered Model of Career Development (Niles, 2011)

- Centerpoint Institute – (centerpointonline.org)

- Colozzi’s re-framing “career to care” (2014)

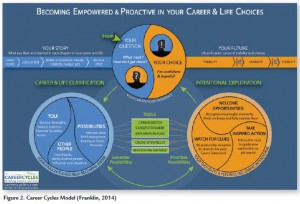

Additionally, Franklin’s (2011) holistic, narrative framework and method of practice for career counseling illustrated in Figure 2 proposes two main processes (1) career and life clarification and (2) intentional exploration. Using a Career Sketch and Career Statement help clients prepare for intentional exploration, minimizing premature and ill-informed choice making. This method has helped individuals in “career pain” experience statistically significant increases in six key measures—hope, optimism, confidence, resilience, curiosity and exploration, and personal growth.

Defining “Career” for A New Era

Jobs provide structure, relationships, and opportunities for finding purpose. Providing career development that empowers learners to be the expert in their own story means understanding that careers are much more than jobs. Franklin’s respect of life’s natural evolution is found within his definition of career, “The full expression of who you are and how you want to be in the world, which keeps on expanding as it naturally goes through cycles of stability and change” (2014). This observation and those that follow acknowledge the changing context of learning, work and aging.

Acknowledging the Context of a New Era

High school-only is connected to low wages and high unemployment…

In a skills-based and knowledge nomad (Feller & Whichard, 2005) rewarded economy, young adults with only a high school education suffer from low wages and high unemployment to a greater extent than their counterparts one and two generations ago (ACT, 2014). Steppingstone jobs are held longer by better-educated more experienced workers as fewer next tier jobs exist. Global business practices, automation and robots devalue manual, routine and low skilled labor. Technical program graduates are often the few high school-only students able to find rewarding entry level employment.

The college experience is increasingly questioned…

College Unbound (Selingo, 2013) and Academically Adrift (Arum & Roksa, 2010) challenge assumptions about the college experience’s value. “Americans have clearly made up their minds about the importance of colleges in preparing students to get good jobs, but measurements of this outcome are murky at best and nonexistent at worst” (Busteed, 2014). When hiring, business leaders say a candidate’s knowledge in the field and applied skills are more important factors than college attended or major (Gallup, 2014).

College debt is increasingly punitive…

Recent college graduates are entering adulthood with record levels of student debt with two-thirds of recent bachelor’s degree holders holding an average debt of about $27,000. Two decades ago, only half of recent graduates had college debt, and the average was $15,000 (Pew, 2014). Over the past decade, the annual rise in tuition, fees, room and board at public four-year schools has been 3.3%, even after adjusting for inflation (College Board, 2014).

More education fails to guarantee work performance…

In the present (and I expect future) workplace, higher levels of education fail to guarantee higher work readiness. Attaining the required education level doesn’t necessarily equip individuals with the skills needed for successful job performance (ACT, 2014). Technological changes cause the relative price of skills to change and the market adjusts by paying for skills more than educational pedigree. Uncomfortable as it might be, four-year college degrees may not provide the security or mobility often professed. Even liberal arts proponents argue for marketable skills (Burning Glass, 2013), and STEM graduates are discovering that precise specializations have short shelf lives.

Career and technical education upgrades holds potential for all learners…

All learning pathways to career roles in demand deserve equal priority and respect (Jarvis, 2013). More relevant, academic and challenging career and technical education (CTE), with strong employer partnerships, and access to expensive high technology produces strong middle skill workers. Growing numbers of “reverse transfer” college graduates have come to understand that making the most of new technologies increases prospects. Since non-technical college grads don’t replace technical workers but rather replace service and retail workers with less education, the role of CTE at the post secondary level is increasingly accessed by unemployed and underemployed college graduates. With 27% of people with certificates and 31% of people with AA degrees earning more than the average BA graduate (Carnavale, 2011), the market power of CTE garners attention.

Growing impatience about skill and innovation gaps…

Critical high value added skills tied to wealth creation and innovation within local economies is increasingly in demand. Uneven talent distribution world-wide is forcing communities and employers to develop innovative ways to find employees, develop internal capabilities, share expertise about promising career development practices, and create regional talent networks.

Careercruising.com, advocates a holistic community career and workforce development approach. Its software brings employer profiles, career coaches and mentors, and diverse workplace learning opportunities together; and, it is accessible 24/7 by secondary and post secondary students, educators, parents and adult career seekers. Rock County, Wisconsin, is one of 15 regional and statewide implementations that enable whole communities to harmonize their efforts to help students and un/underemployed adults connect with employers needing their talents – a comprehensive approach to readiness and community prosperity.

Livable wages, lifelong learning, and self-understanding are ageless goals…

Aging is more recently understood as learning to live rather than to age, and that the roles of learning and work are inseparable from personal relevancy, meaning and purpose. To achieve learning and career readiness over a lifetime, continually upgrading skills, is essential. Although job skills can be acquired through various means (which may include a postsecondary degree), preparatory programs must increasingly offer the necessary skills for specific jobs throughout a career.

Basic academic, lifelong learning, and self-understanding skills are as important as occupation-specific skills during transitions. While job-specific skills are essential for livable wage employment, relevancy and meaning from unpaid but purpose-based activities are critical as well. Purpose research (Strecher, 2013) demonstrates that learning has been found to be correlated with health-related factors including Alzheimer’s, mortality, suicide, weight loss and more. Beyond paid work, remaining relevant demands lifelong learning and making purpose based commitments regardless of age.

A new phase of aging demands readiness too…

Baby Boomers benefit from the incredible longevity dividend shared across the world. Many are reimagining options about leaving paid work, creating the good life (O’Toole, 2005), and seeing aging as getting a “second wind”(Thomas, 2014) to remain as engaged within society as possible. Many extend their work life for financial reasons or professional satisfaction. With more than 10,000 Baby Boomers retiring each day, most are not as well prepared financially as they’d hoped. Returning to post-secondary or some form of lifelong learning is a growing option to finding work and exploring unpaid opportunities. Maintaining purpose, relevance, and connection is foundational to a life reimagined (Leider & Webber, 2013).

Promoting Readiness and Resources for Life Design

The best places to learn and work across one’s lifespan are no longer those promising an education for life or employment security; but rather, those that promote readiness, clarification of career and life choices, and resources for life design. To the degree that the CCR movement can focus beyond youth, time specific events, and graduate “destination rates”, career development will be increasingly relevant and influential. As career counselors and specialists create, adopt, and utilize programs and interventions that encompass lifelong learning, meaningful work, and refined and expanded concepts of aging, greater numbers of individuals (young and older) will be prepared to successfully navigate ongoing lifetime transitions. Only then can we answer affirmatively that CCR looks different than it did in our youth.

REFERENCES

A complete list of references is available upon request from the author.

Author Bio

Rich Feller, PhD (rich.feller@colostate.edu) is Professor of Counseling and Career Development and Distinguished Teaching Scholar at Colorado State University, and Past President of the National Career Development Association.